Clyde Hopkins

1946-2018

As a painter and an educator Clyde had a profound and lasting influence on all those around him - an influence which continues to be assessed with his inclusion last year in the Tate Collection, and solo shows in Barrow, Deal, London and New York in 2022. As the weight and significance of his work is brought to light through exhibition and publication, it becomes increasingly clear that his contribution to contemporary painting, and British abstraction in particular, was extraordinary.

“…Wobbly rectangles all connecting, configurations within configurations, hot colour, imitation surfaces and real surfaces, dots and flat areas, emerging silhouette shapes that recall splashy hieroglyph figures by Miro, and funny island and bay contours that suggest garden evocations by Patrick Heron (they might be earnest homages to Heron or wry jokes on the cult of him): this is all in Clyde’s stuff. Plus the feeling of Robert Motherwell’s Little Spanish Prison (the constructed, charming side of Abstract Expressionism), the feeling of Stuart Davis’s awesomely solid American-style Cubism, Patrick Caulfield’s understated English suburban Pop art, USA cartoons, The Flintstones, funny westerns and towns with the word Gulch in the name: he gives you all these layers of pleasure.”

Hello Painting © Matthew Collings 2007

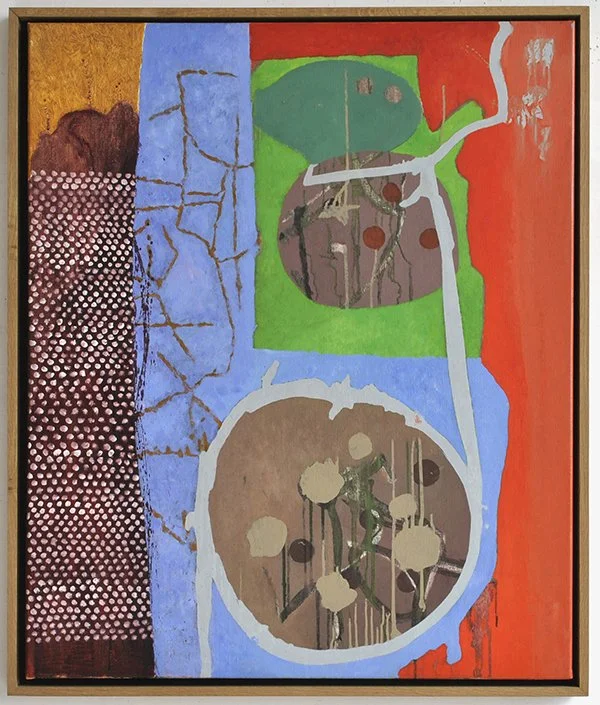

Bread in Pocket, 1990-91, Oil on canvas, 170 x 203cm

“You would expect a body of work, created over a span more than forty years, to display a pattern of development from early attempts, to the mature output where an artist’s ‘signature style’ has fully evolved and is then consolidated. But the paintings of Clyde Hopkins seem to resist this schematic interpretation. Those from the late seventies and early eighties are stylistically different to those produced in the late eighties. Another change occurs in the nineties and from 2008 or thereabouts the paintings seem to take on characteristics almost the opposite of those to be found in work from earlier in his career. So, instead of one signature style, there are several.

Each of these signature styles is fully resolved and sufficient, rather than marking an evolutionary stage in an ongoing narrative. Each deploys an established set of procedures and material properties. The pattern that emerges is more a series of brackets rather than a smooth gradient, each bracket containing a group of works with similar visual qualities.”

David Sweet

“'Bread in Pocket' 1990/91 brings in some familiar elements from the 1980s. A line is dropped and then found; it is both tentative and definite. Colour is translucent as well as opaque, the ground is absorbent and breathes and yet here separate elements start to emerge. It is important to remember that very much earlier painting made a diffuse sensaround, a leafy watery sort of place. The total layered translucent play of veils across the canvas creates an imaginative space which is as much about the process of doing and making as it is about depth.”

Sacha Craddock

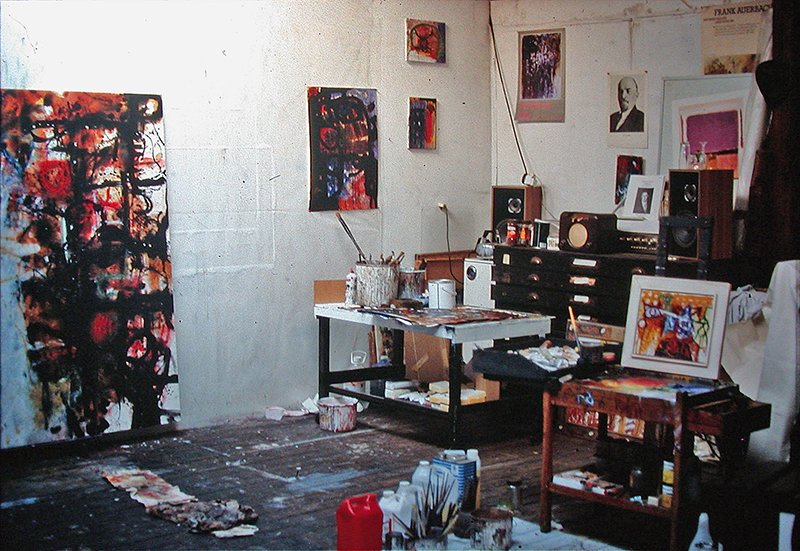

Studio, November 1989

“…the merit of any work of art lay in its capacity for disturbing the spectator’s equilibrium – for presenting him or her with a vision of defiance, sometimes brutal and sometimes gentle. That is more or less how I see Hopkins’ new paintings. They are serene and gentle in certain parts, nervous and anguished in others. In certain respects they fall into a conservative mold – certainly adhering to the tenets of large-scale abstraction painted in an avant-garde-ish spirit. Yet in other ways they conform to a more unfamiliar and more daring tradition: the quasi-political tradition of more or less open disgust.”

Brandon Taylor

Chaunticlere, 1989, Oil on canvas, 183 x 170cm

Sulfure et Zinc, 1990, Oil on canvas, 192 x 176.5cm

Market Gardening, 1991, Oil on canvas, 135 x 112cm

“one of the great qualities of Hopkins’ new paintings, as i see them, is to have abandoned the particularly English problem of whether abstract art needs to be in some painterly relation to landscape. He has decided it would be better to avoid the term entirely. On the contrary it is through recollections of Dali, Miro, even Picasso, that the artist has remembered how the sun can sharpen the shadows, heat the landscape, and probably addle the brains. Are we madder or saner now? It makes no difference. In Hopkins’ new world, it is advisable to try both.”

Brandon Taylor

Over Peenemunde, 1993, Oil on linen, 91.5 x 76cm

“The elements in Hopkins’ work seem to come from strikingly different, even contradictory, traditions, as if he is seeking to cover extremes of expressive language, rather than occupy a unified middle ground. The juxtaposition produces a peculiarly complementary effect, as though two implacable opposed artistic visions had collided in the same work. The result is an increase in intensity so great that the contents of the painting seem to pass through a tangible ordeal, a sort of visual pain barrier, which strips them of lyrical compromise, and aesthetic consolation and delivers, in the place of these lesser pleasures, the unmistakable rewards of serious poetry.”

David Sweet

Untitled, 2002-3, Oil on canvas, 127 x 102cm

Last Old V5, 1998, Oil on linen, 91 x 76cm

Discrete Concretism, 2000, Oil on canvas, 76 x 61cm

The Crate Jerked Skyward as Tibbets Contemplated #2, 2000-2001, Oil on linen, 61 x 51cm

A Hillbilly in Paris, 2001, Oil on linen, 61 x 51cm

Bulverhythe, 2001-2, Oil on canvas, 76 x 61cm

Sycamore, 2003-4, Oil on linen, 61 x 51 cm